Some people might say that my Dad has had his fair share of bad luck. First he was forced into retirement, then there was the divorce that sent the family into turmoil and finally the icing on the cake, the big C. Now this is not a story about the trial and tribulations of my Dad’s life, but of how his life was saved. But first, I think it would be good to briefly explain some of my Dad’s health issues that were, in part, the reason for this cascade of unfortunate events.

My Dad was born with the inherited disease haemophilia, a condition that prevents the clotting of blood. This means that any bruises and cuts that a normal person might brush off as minor could quickly become more serious. Early in his training as a doctor, my Dad had an accident that, due to the haemophilia, required a blood transfusion. At this time in history pooled blood donations were used to treat such bleeding however, the NHS had low stocks and this meant blood had to be sourced from America who, at the time paid for blood donations, attracting the likes of prostitutes and drug addicts. This blood was not tested properly and, regrettably, many people were infected with diseases such as Hepatitis and HIV. My Dad was unlucky enough to get Hep C, a virus that damages the liver causing cirrhosis (severe scarring) and which is the number one cause of hepatic cancer. Many people have died from this historical mishap, some living over the age of 30 with no knowledge that they were carrying the virus.

After finishing a contract as a research assistant I returned home to live with my Dad. I had decided that in the time before starting a PhD I would travel the world with the old man, who had long pleaded for a travelling companion to help complete his bucket list and share the memories. However, this was not to be as in late November 2014 my Dad sat me down to tell me that his liver cirrhosis had developed into a cancer. Although a shock, I was somewhat impassive to the news, in part because as a teen I had battled with the knowledge that my Dad was ill of health and good news was not around the corner. My mind focused on the future and that was when I offered to donate my liver – it was a no brainer.

Let us pause for a second and marvel at the liver and the feats that modern medicine can achieve.

The liver is the largest organ in the human body and, as well as having the ability to regenerate itself, it provides a number of essential roles (e.g. detoxification, bile production, protein production, storage of vitamins and minerals etc.). Armed with the steadiest of hands surgeons are able to transplant a part of a donor’s liver into a recipient. With regenerative abilities the liver grows to be fully functional. However, rewiring the new liver is a fiddly job and the whole process can take up to 12hrs.

But wait, why donate when a cadaver could be used? Waiting for a non-living liver donation has no guarantee as there are a number of boxes that first need to be ticked; first you need a cadaver, then you need the right blood group and finally the liver needs to be in a suitable condition. Not only this, but there is a waiting list and so before it is your ‘turn’ and all the right conditions are met, there is the chance that the cancer could have developed to a point where transplant is no longer feasible. Long story short, we were later advised that a living donor would be the best option and as I said earlier it was a no brainer.

After offering to be a donor I stopped drinking alcohol and began the various tests to see if my liver was a suitable candidate. Potential donors are put through rigorous assessments including a CT scan, a MRI scan, endless blood tests, a psychological assessment and a liver biopsy. All these could have been done in the space of a week, but the hospital eked the process out, adamant that I should have at least three months to think about my decision. This provided plenty of time to read up and worry about the various stats and potential morbidities. For instance, there is a 30% chance of a mild morbidity (bleeding, bile leak, infection), a 5% chance of a serious morbidity (anything that may cause long term health complications) and <1% chance of mortality. After the operation most donors are in the intensive care unit for 2 days and are discharged after 7 days, making a full recovery within 6 months. To be honest, none of this really fazed me, instead I was more concerned with the idea of having a catheter and, after I had come to terms with that, I became obsessed with the idea of waking up in intensive care, confused and with a breathing tube down my throat.

After the MRI and CT scans I was told that, although they were happy to continue, I was high risk and they would like to see if there was anyone else in the family that may consider donating. The biggest cause of death in liver transplants is liver deficiency. This is where there is not enough liver for the body to adequately function and any minor morbidities quickly become big problems. Unfortunately, the size of my liver meant that I would have to give up 66% in order to meet my Dad’s minimum requirements. This put me in the high risk category as the risks go up exponentially when donating between 50-70% of your liver.

With great foresight my younger brother (Deraj a.k.a Day) stopped drinking when I did in preparation of potentially offering his liver. As the oldest, I had hoped my ‘coming forward’ would not only extend my Dad’s life, but also protect my brother and sister from the harrowing experience of donation, so for me this was not an option. However, the decision was out of my control and arguing with the professor who would lead the transplant proved futile. In truth I also thought testing my brother was a waste of time, with Day being smaller in stature, I never believed he would have a big enough liver to be less at risk. Despite my feelings of frustration towards the situation I began focusing my attention on supporting my brother. I was in a fortunate position to reassure and accompany Day when it came for him to be assessed.

The CT scan involves an x-ray and requires a contrast medium (or dye) which is pumped into the body to highlight specific blood vessels. The dye is administered via a device called a cannula and causes a warm sensation as it travels through the body. I explained this to Day and added that the sensation reminded me of Captain America when he was pumped with the drug that gave him super human strength. Day contributed to my superhero themed description by pretending to be Spiderman.

After the CT and MRI scans it was confirmed that Day would be the donor. He would need to donate 56% of his liver, whereas I would have to donate 66%. I didn’t take the news well and dipped into a negative mind set, comforted only by a statistic that 1 in 4 donors reach the final transplant stage. A few days later I called Day up, asking him how he felt about the decision. He was super keen, but the gravitas of the situation was beginning to sink in. I opened up and told him about all the worries I had had when I was going to be the donor and the sleepless nights I had had thinking about it all. I hoped that by doing this it would provide some reassurance that it was OK to be scared, even about the most trivial things such as having a catheter removed. This turned out to be a fairly amusing discussion about our concerns that allowed me to help fill in the gaps with the weeks of reading I had already done.

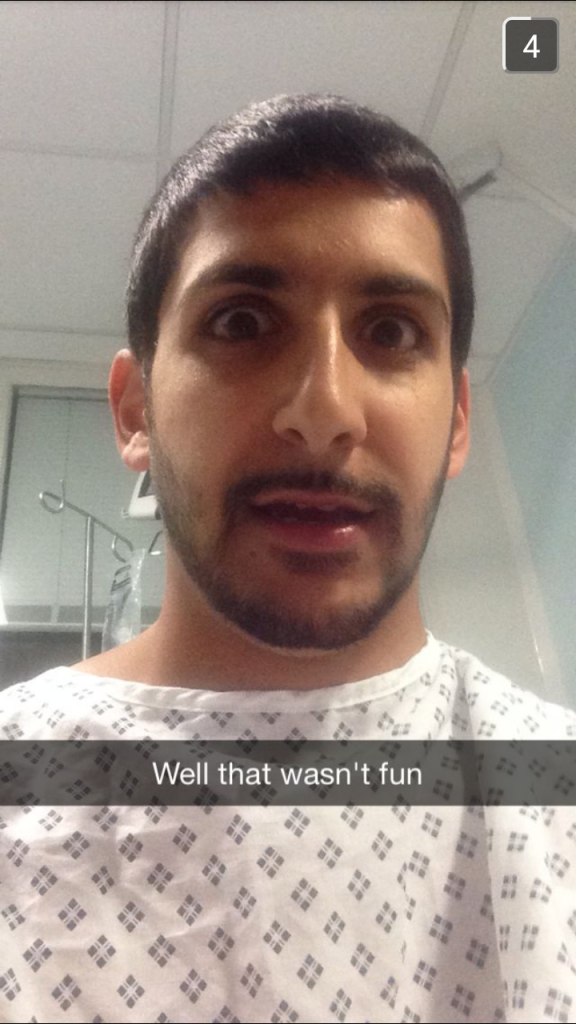

One of the final and most daunting assessments (which I did not have to endure) was the liver biopsy. The biopsy, due to its invasive nature, is the final assessment and involves taking samples of the liver to check its function is adequate. The donor is put under local anesthetic and a needle is fed through a vein in their neck (the jugular) to reach the liver. Needless to say both Day and myself were anxious. However, our angst was short lived for the whole process was over before Day had even realised it had started, taking a mere 10 minutes. Day argued that he didn’t even think the anesthetic had time to have an effect, a claim that we hotly debated. It was later that evening when the anesthetic wore off and the pain set in. Day slowly made his transition from being a cheeky little brother to a decrepit old man with a bad case of stiff neck. It was when Day first began grimacing in pain that I started giving the knowing look of ‘I told you so’ which would set us both off laughing and, inevitably, ending in Day once again grimacing.

Once all the assessments were complete the hospital confirmed the operation would take place on the 17th June 2015. The night before the operation both Dad and Day stayed at the hospital with the aim to get Day into theater the next day at 7am, followed by Dad at 11am. To distract Day from the worry of the operation, and much to his displeasure, the hospital arranged for him to have an enema. The look on Day’s face when they told him was amazing, out of all the experiences so far, this was the one that would haunt him the longest. When we told Dad he went into a mild panic, questioning the nurses as to whether or not he too had to have one. When it was revealed that he did not Dad responded with a big smile and sigh of relief, followed by a bellowing laugh which Day did not appreciate.

That night I don’t think anyone got a good night sleep and this was especially true for Day and Dad. I can’t begin to imagine what was going through their minds as they lay in the hospital beds mentally preparing for the challenging journey that waited for them on the horizon.